Why Big-Ticket Property Is No Longer Just for Billionaires

Until recently, investing in multimillion dollar real estate projects sounded like something that happened in glass towers between people who travel by helicopter. Yet by 2025, a growing slice of these deals is quietly funded by dentists, IT engineers, small business owners and even cautious retirees. The numbers explain why: institutional‑grade real estate has historically delivered 8–12% annualized returns over long horizons, with relatively low correlation to stock markets. What changed in the last decade is access. Online platforms, more transparent regulation, and the boom in “fractional ownership” stripped away many of the old gatekeepers. If you’ve ever wondered how people get into a $30M office tower or a $50M multifamily complex with less than seven figures in the bank, this is where the landscape now looks very different.

Short version: you still need capital, patience and due diligence skills—but you no longer need to be ultra‑rich or work at a private equity firm to get a seat at the table.

What Exactly Are Multimillion-Dollar Real Estate Projects?

At this scale, we’re usually talking about institutional‑grade assets: a $40M apartment complex in Dallas, a $25M logistics warehouse near Rotterdam, or a $60M mixed‑use project in a growing suburb of Atlanta. These aren’t the two‑flat buildings you see on YouTube flipping channels. They’re large commercial or residential income‑producing properties with dozens—or hundreds—of tenants, professional management, and detailed financial models behind them. When newcomers ask how to invest in large commercial real estate deals, they’re essentially asking how to plug into this existing professional ecosystem without getting crushed by complexity or hidden risks.

Think of it as joining a cargo ship crew rather than renting a paddleboard at the beach.

Three Main Ways Beginners Access Big Deals

1. Real Estate Syndications

A syndication is a group investment. A “sponsor” (also called the operator or GP) finds the deal, negotiates the purchase, arranges financing, and runs the property. Passive investors (the LPs) put in capital but don’t manage the day‑to‑day. A typical $20M apartment acquisition might be financed with 65% debt ($13M from a bank) and 35% equity ($7M from investors). If the sponsor raises that $7M from 70 investors, each might put in $100,000. That’s where a beginner guide to real estate syndication investing really starts: understanding that you’re buying a slice of an organized business plan, not a random “piece of a building.”

The legal structure is usually an LLC or limited partnership, and your name goes on the cap table, not on the property deed.

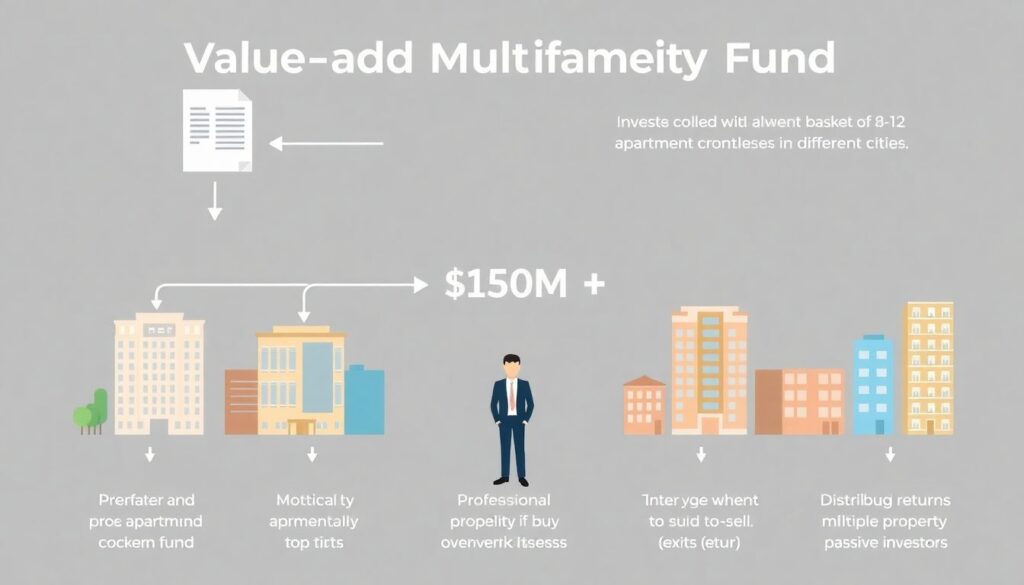

2. Private Real Estate Funds

Instead of investing in a single property, you invest in a fund—basically a basket of deals. A value‑add multifamily fund, for instance, might raise $150M, then acquire 8–12 existing apartment complexes across different cities. The manager (the GP) chooses the assets, times the exits, and distributes profits. Minimums vary widely: some niche funds in 2025 still start at $250,000, but newer online managers have brought that down to $25,000–$50,000. The trade‑off is control. You rarely get to cherry‑pick individual properties, but you gain diversification and professional curation you’d struggle to replicate solo.

You’re betting on the manager’s track record and strategy rather than a single building’s story.

3. Online Platforms and Fractional Ownership

The best platforms for investing in big real estate projects essentially aggregate syndications and funds, wrap them in a user‑friendly interface, and handle the legal plumbing. In 2025, platforms in the US, UK, EU, India and the Middle East offer stakes as low as $5,000–$10,000 in office parks, data centers, industrial portfolios and large rental communities. Many deals are still restricted to accredited investors, but regulation is slowly widening. These platforms don’t remove risk; they just standardize documentation, track performance, and typically pre‑screen sponsors. For beginners, that “curated shelf” can reduce the chance of walking into an obviously flawed deal.

You’re still responsible for reading the fine print; the platform doesn’t do your thinking for you.

Real-World Example: From $75K Savings to a $32M Apartment Deal

Imagine a mid‑career software engineer with $75,000 in savings earmarked for long‑term investments. Through a reputable syndication platform, she encounters a 250‑unit Class B apartment complex in Phoenix priced at $32M. The sponsor is raising $10M of equity with a $50,000 minimum per investor. She invests $50K. Over five years, the plan is to renovate units, push rents by 12–15%, refinance, then sell. Projected IRR is 14% with an equity multiple of 1.8x. In a realistic mid‑case outcome, her $50K could turn into about $90K across annual distributions plus profit at sale. She never visits the property, but she reviews monthly occupancy data and quarterly financials, and sits in on webinar Q&As with the sponsor.

She hasn’t “bought an apartment building”; she’s bought a small, clearly defined economic interest in its cash flow and eventual appreciation.

Technical Note: Minimum Investment and Deal Math

When people ask about the minimum investment for large scale real estate investments, they’re usually surprised by the range. In 2025, direct syndications from experienced sponsors often require $50,000–$100,000 per deal. Some raise their minimums in hotter markets to filter out unserious capital or administrative overhead from tiny tickets. Online platforms may push this down to $5,000–$25,000 because they handle a high volume of investors and automate reporting. But the underlying math doesn’t change: on a $30M acquisition with 70% debt and 30% equity, the sponsor must assemble $9M of investor equity. Whether that’s 90 people at $100K or 900 people at $10K affects complexity, but not the underlying risk/return structure or the debt load.

What You Actually Own (and What You Don’t)

As a passive investor, you don’t own a floor or a specific unit; you hold membership or partnership interests in an entity that owns the asset. This distinction matters when something goes wrong. If a tenant slips and falls, they sue the property‑owning entity, not you personally. Your risk is generally limited to your invested capital—assuming the deal wasn’t structured with personal guarantees that extend to LPs (rare and usually a red flag). You also don’t make tactical calls: rent levels, renovation budgets, whether to sell or refinance—that’s all on the sponsor. You do, however, have rights spelled out in the operating agreement: access to financial statements, voting on certain major events, and a clear hierarchy of who gets paid first.

In practice, you’re more like a shareholder in a private company than a landlord with keys.

Technical Note: Capital Stack and Payout Order

A typical capital stack in a $40M project might look like this: $26M senior bank loan at 5.5% interest, $4M preferred equity at an 8–10% fixed return, and $10M common equity from the sponsor and LPs. In liquidation or sale, the senior lender gets paid first, then preferred equity, then common equity shares whatever is left. If the project underperforms, there might be enough to pay the bank and partially satisfy preferred investors, leaving little or nothing for common LPs. Many beginners underestimate how the capital stack shapes risk: moving from common equity to preferred equity usually trades upside potential for a clearer, more predictable coupon‑like return profile.

Understanding where you sit in that stack is more important than any glossy brochure.

Risk: Not Just “Will the Building Be Full?”

Vacancy risk is obvious, but big deals carry several other moving parts. There’s financing risk: many projects use floating‑rate debt; when rates spiked from near‑zero to above 5% between 2022 and 2024, countless operators saw their interest expense double or triple. Some were forced to sell early at unattractive prices. There’s execution risk: a sponsor might assume they can renovate 20 units a month; if labor and permits slow that to 8 units, the entire timeline shifts. Then you have macro risk: remote work undercut some office towers, e‑commerce boosted logistics warehouses, and demographic flows reshaped demand for Sunbelt apartments. When you evaluate a deal, you’re evaluating how fragile the business plan is to these shocks.

The property isn’t a static asset; it’s an operating business wrapped in concrete and steel.

Technical Note: Stress Testing a Deal

Professionals rarely accept rosy base‑case projections at face value. They “stress test” assumptions: what if interest rates are 1.5% higher at refinance than modeled? What if exit cap rates are 0.75% higher, lowering the sale price? What if rents grow at 1% instead of 3% annually? A quick sanity check might ask: if net operating income ends up 15% below projections, does the project still cover debt service with a 1.2x DSCR (debt service coverage ratio)? If dropping occupancy from 95% to 88% turns cash flow negative, that’s a fragile deal. Beginners don’t need to build full models, but they should at least look for these “what if” scenarios in offering memoranda, or ask pointed questions on investor calls.

If a sponsor can’t explain downside cases clearly, that’s usually your answer.

How to Actually Start: A Practical On-Ramp

Before wiring a single dollar, treat this like learning a foreign language. Spend a few weeks reading investor decks from multiple sponsors. Join webinars as a listener only. Ask operators how they survived the 2023–2024 interest‑rate reset; their answers will reveal a lot about risk management. When you’re deciding how to invest in large commercial real estate deals for the first time, consider starting with a smaller ticket in a straightforward asset class—say a stabilized multifamily property in a market with growing population and diversified employment. Avoid exotic structures, ground‑up high‑leverage construction, or luxury projects that depend on perfect timing.

Your opening goal is not to shoot the lights out; it’s to learn the process while preserving capital.

Technical Note: Due Diligence Checklist for Beginners

You don’t need a Wall Street background, but you do need a consistent checklist. Start with the sponsor: How many full‑cycle deals (bought, operated, sold) have they completed? What’s their worst deal and what did investors actually get back? Then the market: Is population and job growth above the national average? Are there major employers, or just a single industry? For the deal itself: What’s the in‑place cap rate versus market comps? How aggressive are rent growth assumptions? Finally, legal and fees: How is the promote structured, and what fees does the sponsor charge (acquisition, asset management, refinance, disposition)? Write these questions down and reuse them; patterns—both good and bad—will quickly emerge.

Consistency beats cleverness when you’re new.

Platforms, Regulations and the 2025 Landscape

By 2025, regulation‑driven transparency has reshaped the online space. Many jurisdictions now require standardized performance reporting and clearer risk disclosures, especially for platforms that target non‑accredited investors. The best platforms for investing in big real estate projects publish historical deal performance, including losers, not just top‑quartile winners. They often provide stress‑tested scenarios and standardized IRR calculations instead of marketing‑friendly “projected annualized returns.” Artificial intelligence is increasingly used to screen deals—flagging unrealistic underwriting and cross‑checking sponsor claims against market data. This doesn’t eliminate bad actors, but it raises the bar. The flip side is more competition: good deals are often fully subscribed within hours, and sponsors can be choosy about who they accept.

For investors, selection has never been broader, but the noise level is higher than ever.

Technical Note: Fees and Net Returns

In real estate, what you keep after fees matters more than headline IRR figures. A common structure is “2 and 20”: a 2% annual asset management fee on equity plus a 20% promote above a hurdle, often 8%. But variants abound: 1.5% plus a 70/30 split after investors receive their preferred return; or higher up‑front acquisition fees in exchange for lower ongoing costs. For a five‑year deal with a 16% gross IRR, fees might drag the net IRR down to 12–13%. That difference compounds heavily over multiple cycles. When comparing opportunities, line up the projected net equity multiple and IRR, not just pre‑fee numbers, and be wary of structures where sponsors get paid handsomely regardless of performance.

Incentives should clearly reward them only after you’ve been paid your due.

Forecast: Where Big Real Estate Investing Is Headed by 2030

Looking ahead from 2025, several currents are reshaping this space. First, institutional capital and retail capital are converging. Expect more “semi‑liquid” private real estate funds where you can request quarterly redemptions, blurring the line between REITs and private syndications. Second, certain sectors look set to grow structurally: data centers, cold storage, last‑mile logistics, senior housing and workforce rentals in cities with chronic supply shortages. Demographics and digitalization are powerful tailwinds. Third, regulators are likely to keep nudging access wider while tightening disclosure standards, especially after any high‑profile failures. By 2030, it’s realistic that a middle‑class investor with disciplined savings and solid education could build a diversified $250,000 portfolio spread over 15–20 large projects globally.

The bar for professionalism will rise: sloppy underwriting and optimistic fairy tales won’t age well in this environment.

Technical Note: Role of Technology and AI

As of 2025, AI is already parsing leases, predicting tenant rollover risk, and modeling rent scenarios from macroeconomic data. For investors, that means more objective benchmarking: algorithms can flag when a sponsor’s rent growth assumptions sit in the top 5% of local history—an instant caution signal. On the operational side, smart‑building tech pulls down energy costs and improves maintenance scheduling, supporting net operating income. Over the rest of the decade, expect transactional friction to fall: blockchain‑based registries may simplify cap tables and secondary trading of LP interests, offering liquidity that used to be unheard‑of. None of this removes fundamental risk, but it does make information more symmetric between sponsors and investors.

Better data doesn’t guarantee better decisions—but it punishes lazy decisions much faster.

Putting It All Together: A Sensible Beginner’s Roadmap

If you’re considering stepping into this world in 2025, frame the next two years as an apprenticeship. Start by educating yourself with free materials from multiple sponsors and platforms. Clarify your risk tolerance and time horizon: are you comfortable locking up money for 7–10 years, or do you need potential liquidity sooner? Begin with one or two modest‑sized positions in boring, income‑oriented assets before experimenting with development or niche sectors. Document your reasoning for each investment and revisit it annually as new data arrive. Over time, the jargon will fade and patterns will stand out: which operators consistently hit their projections, which markets shrug off cycles, and what structures align incentives cleanly.

The goal isn’t to guess the next hot sector; it’s to steadily build exposure to real assets that can compound for decades while you sleep.