Why Retirement Income Planning Feels So Hard (And Why You Can’t Wing It)

Most people enter their late 50s with a decent 401(k), some savings, maybe a paid‑off house — and absolutely no clear idea how that pile of money turns into a reliable paycheck. Accumulating assets and designing an income stream are very different problems. In practice, retirement income planning is about answering three questions: how much you can safely spend each year, where that money should come from (accounts, pensions, Social Security, rentals, dividends), and how to protect yourself from living too long, market crashes, and inflation. Treat it like building a “personal pension”: a structured system, not just tapping an investment account whenever you need cash.

—

Step One: Map the Cash Flows, Not Just the Portfolio

From Net Worth Snapshot to Income Blueprint

The first practical step is to stop thinking only in terms of “I have $700,000 saved” and start framing everything as cash in vs. cash out. You list your essential expenses (housing, food, utilities, insurance, basic healthcare) and your discretionary ones (travel, hobbies, gifts). Then you line those up against guaranteed income sources: Social Security, pensions, annuities, maybe rental contracts. The gap between expenses and guarantees is what your portfolio must reliably cover. When professionals deliver retirement income planning services, the good ones always begin with this cash‑flow view, not with product pitches. It forces a realistic conversation: maybe the issue is not investments at all, but an expensive house or too much “mandatory” lifestyle.

—

Technical block: How to quantify the gap

A quick working formula: Annual Required Portfolio Income = (Total Annual Spending – Guaranteed Income) / (1 – Tax Rate on Distributions). Suppose a couple needs $80,000 per year after tax, has $40,000 from Social Security, pays about 15% effective tax on withdrawals. Required portfolio income is ($80,000 – $40,000) / (1 – 0.15) ≈ $47,000. If they hold $900,000 in investments, that’s a withdrawal rate of around 5.2%. Immediately you can see the tension: most research suggests sustainable long‑term withdrawal rates hover near 3.5–4.5% depending on assumptions. Without a detailed spreadsheet, this rough math already tells you whether you’re in a “tight,” “comfortable,” or “surplus” scenario and frames what kind of strategy you must adopt.

—

Three Core Approaches: Safety First, Market First, or Hybrid

1. Safety‑First: Create a Floor, Then Add Upside

The safety‑first approach prioritizes setting a hard floor under your essential spending. You lock in predictable income to cover the basics, often using a mix of Social Security optimization, pensions (if you have them), and possibly immediate or deferred annuities. Anything left in your portfolio can then pursue growth for discretionary goals. In real life, this appeals especially to people who remember 2008 vividly and lose sleep when markets swing. For instance, a 65‑year‑old single retiree with $600,000 might put $250,000 into an immediate annuity plus Social Security to cover $3,500/month fixed costs, holding the remaining $350,000 in a diversified portfolio aimed at moderate growth. The trade‑off: more peace of mind, but less liquidity and possibly lower total inheritance for heirs.

—

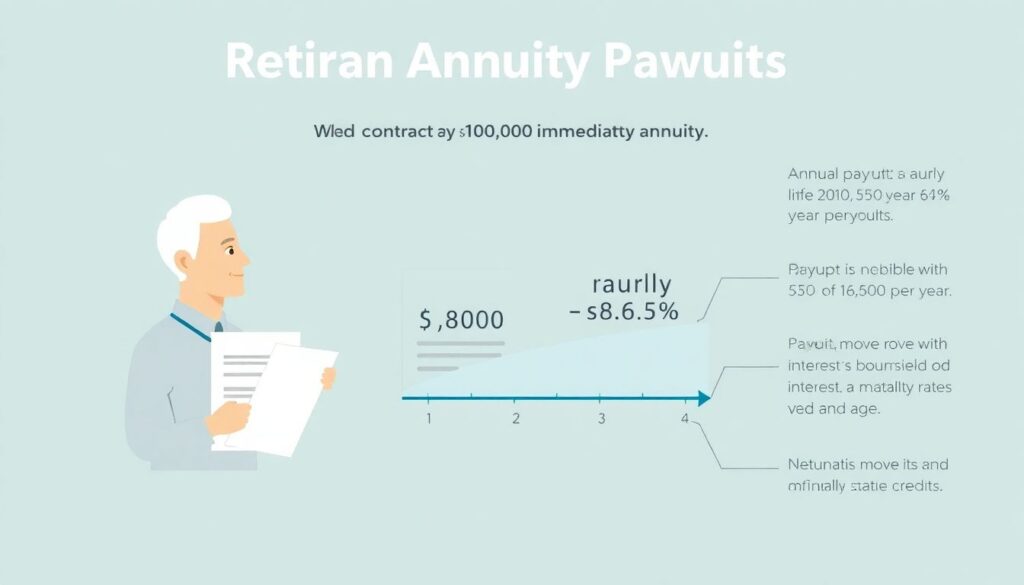

Technical block: How much income can an annuity really buy?

Payouts move with interest rates and age. As of 2024, a 65‑year‑old buying a life‑only immediate annuity for $100,000 might receive roughly $5,800–$6,500 per year (5.8–6.5% payout), depending on provider and options. This is not a “yield” like a bond; it combines interest, principal return, and mortality credits. The insurance company can pay more than a bond portfolio because some annuitants will not live as long as others. The risk is loss of flexibility: once purchased, it’s usually irrevocable. When you plug this into a retirement income calculator for guaranteed monthly income, test different inflation assumptions and survivor benefits; each add‑on reduces the starting payout but might fit your family’s risk profile better.

—

2. Market‑Driven: Total Return with Dynamic Guardrails

The market‑driven model keeps everything invested and simply draws a percentage each year, adjusting gradually. Classic research promoted a fixed 4% rule, but modern practice prefers flexible “guardrail” systems. For example, you might start at 4.5%, increase withdrawals with inflation, but cut spending by 10% if the portfolio falls more than 20%, and allow an increase if it grows strongly. This gives you higher expected long‑term income and keeps assets liquid, which is useful if early‑retirement healthcare or family emergencies arise. A couple with $1.2 million invested might start near $54,000/year before tax, knowing they’ll tighten the belt during bear markets. Psychologically, this approach works best for people who can accept volatility and adjust lifestyle without panic.

—

Technical block: Evaluating withdrawal sustainability

To stress‑test a withdrawal rate, planners often run Monte Carlo simulations: thousands of random market paths based on historical volatility and correlations. You’d test, say, a 4.5% starting withdrawal, 30‑year horizon, 60/40 stock‑bond mix. If the plan shows an 85–90% probability of not running out of money, it’s generally considered robust. However, assumptions about future returns matter a lot; using historical US equity returns might be optimistic. Conservative models might use 3–4% real returns for stocks and 0–1% for bonds. If simulation results drop below 70% success, it signals the need to lower spending, delay retirement, or change the investment mix, rather than hoping markets will be unusually kind.

—

3. Hybrid Buckets: Matching Time Horizons

Hybrid “bucket” strategies try to merge psychological comfort with math. You segment money by time horizon: near‑term cash, mid‑term bonds, long‑term growth. Bucket 1 might hold 2–4 years of essential expenses in cash and short‑term bonds, Bucket 2 another 5–7 years in conservative fixed income, and Bucket 3 in equity‑heavy portfolios for growth beyond year 10. Retirees then refill Bucket 1 from Bucket 3 during good years, skipping replenishment during crashes. Many people find this more intuitive than staring at one large fluctuating balance. In practice, best retirement income strategies for retirees often combine buckets with Social Security optimization and maybe a small annuity for longevity protection, giving structure without over‑committing to illiquid products.

—

Real‑World Case Studies: Same Assets, Different Paths

Case 1: “I Never Want to Worry About the Light Bill”

Maria, 66, has $800,000 in savings, $2,000/month expected from Social Security, and no pension. Her essential expenses are about $3,200/month; discretionary another $1,000. She is deeply loss‑averse. A safety‑first planner might use $250,000 to buy a lifetime inflation‑adjusted annuity paying roughly $900–$1,000/month initially, then help her delay Social Security to age 70 if possible, raising her benefit to around $2,600. That combination could fully cover essentials with built‑in inflation protection. The remaining $550,000 stays invested conservatively for travel and unexpected costs. Could she end up with less total wealth than if she stayed fully invested? Yes. But her explicit goal is emotional security, and the plan is tailored to that preference rather than to theoretical maximum returns.

—

Case 2: “I’m Comfortable with Markets, Just Don’t Let Me Blow It”

James and Linda, both 62, saved $1.4 million and will get a combined $3,600/month in Social Security at 67. They’re healthy, plan to retire at 63, and want flexibility for big early‑retirement travel. A market‑driven hybrid plan might set a 4.5% initial withdrawal from a 60/40 portfolio (~$63,000/year before tax), plus $20,000 from part‑time consulting the first five years. They agree to a firm rule: if portfolio value ever drops below $1.05 million, withdrawals automatically cut 15% until recovery. They postpone Social Security to 67, using the portfolio to bridge income. Compared with Maria, they accept variability to maintain liquidity and upside. Stress‑tests might show an 80–90% success rate over 30 years, acceptable for clients who can adjust spending when necessary.

—

Passive Income Myths vs. Reality

What “Passive” Usually Looks Like in Retirement

Many people search for how to generate passive income in retirement and imagine a simple checklist: buy rentals, pick high‑dividend stocks, relax. In reality, each “passive” stream carries specific risks and workload. Rental property can diversify cash flow and hedge inflation, but also adds tenant risk, vacancies, repairs, and local market exposure; a paid‑off $300,000 duplex might net $1,500–$1,800/month after realistic costs, but only if managed competently. High‑dividend stocks concentrate risk in certain sectors and can see payouts cut during downturns. REITs, covered‑call ETFs, or private credit funds add complexity, correlation, and sometimes opaque risks. True retirement income planning integrates these assets into a total‑return framework instead of chasing yield in isolation.

—

Technical block: Yield chasing vs. total return

A dangerous pattern is treating yield as “free” income. Suppose Bond Fund A yields 3% with low credit risk, while Fund B yields 7% by holding lower‑quality debt. If your portfolio goal is a 4% withdrawal rate, reaching for 7% yield doesn’t make your plan safer; it just swaps price volatility and default risk for the illusion of higher income. Total‑return planning starts from required spending and invests for risk‑adjusted growth, then builds a systematic withdrawal policy that might involve selling appreciated shares in low‑yield assets. The math of compounding doesn’t care whether cash comes from dividends, interest, or strategic sales; what matters is after‑tax, after‑inflation sustainability at your chosen risk level.

—

Advisors, DIY, and When to Pay for Help

Should You Go It Alone or Bring in a Specialist?

Doing this solo is possible, especially for numerate investors comfortable with uncertainty. Still, decumulation mistakes are often irreversible: overspending early, poor tax sequencing, or ignoring healthcare risk can’t be fixed easily at 78. That’s why many people search to hire retirement financial advisor near me once they approach their “work optional” date. The value isn’t just picking funds; it’s designing Social Security timing, Roth conversion windows, tax‑efficient withdrawal order, rebalancing rules, and contingency plans. A competent advisor should be able to show you, in hard numbers, how their recommendations alter projected success rates and potential taxes paid over 30 years, and should be transparent about fees relative to this quantifiable benefit.

—

Technical block: Tax‑efficient withdrawal sequencing

A common high‑impact tactic is coordinating withdrawals across taxable, tax‑deferred, and Roth accounts. One frequent pattern: in early retirement (before Social Security and RMDs), draw from taxable accounts while performing partial Roth conversions up to a target tax bracket (for example, filling the 22% bracket). After Social Security and RMDs begin, tap IRAs only as required and supplement with taxable/Roth as needed to control brackets and Medicare IRMAA surcharges. Over 25–30 years, this can reduce lifetime taxes by six figures for some households. Software used in retirement income planning services can model these sequences, but even a spreadsheet with projected balances and bracket thresholds provides better insight than guessing year‑by‑year.

—

Using Calculators and Guardrails Instead of Guesswork

How to Use Tools Without Being Misled by Them

Online tools are useful if you treat them as rough diagnostics, not oracles. A basic retirement income calculator for guaranteed monthly income can estimate how much annuity‑style cash flow your assets might buy or how sensitive your plan is to retirement age and spending changes. Run multiple scenarios: retiring at 63 vs. 67, downsizing housing, or trimming $500/month from discretionary travel. Then layer in what the calculator often ignores: long‑term care risk, tax regime changes, and your emotional tolerance for volatility. The goal is not to hit a single “magic number” but to define a corridor of acceptable outcomes with clear triggers for adjusting spending or investment mix when markets or health realities shift.

—

Bringing It All Together: A Practical Playbook

Designing Your Personal Pension

A robust plan tends to blend elements from each approach. You might secure a base floor of income for essentials using Social Security optimization and modest annuitization, then run a diversified total‑return portfolio with clear withdrawal rules for discretionary spending, implemented through a bucket structure for psychological comfort. Along the way, you document: your target withdrawal rate, how it will change after major life events, which account you tap first each year, and when you will reconsider the plan (for example, after a 20% portfolio drawdown or a major health diagnosis). Retirement isn’t a one‑time decision at 65; it’s an ongoing engineering problem. Treating it this way, with conscious trade‑offs instead of vague hope, is what turns a pile of savings into a durable, livable income stream.