Why infrastructure bonds suddenly look interesting again

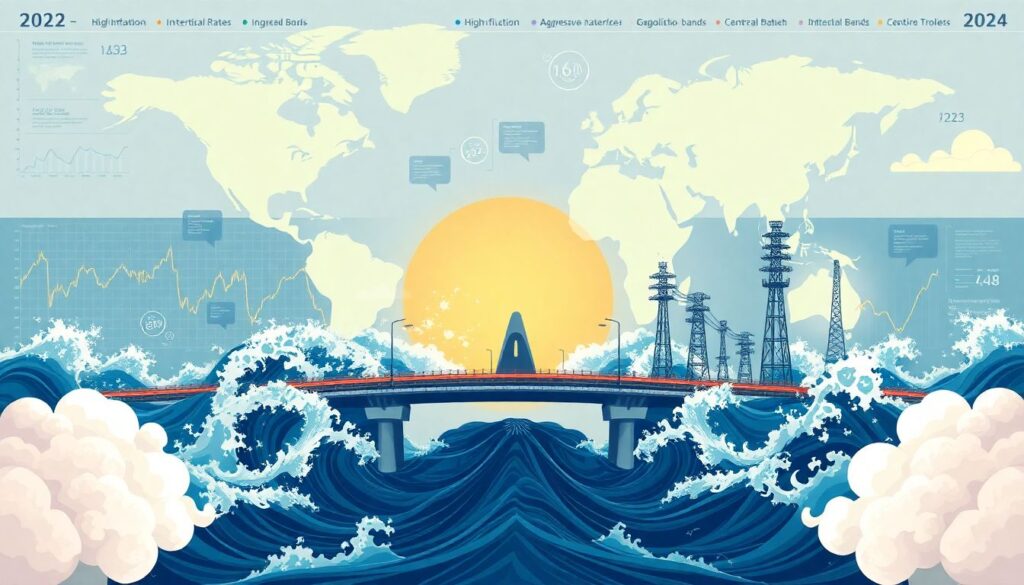

If you feel whiplash from markets over the last few years, you’re not alone. From 2022 to 2024, we went from “free money” rates to the fastest global hiking cycle in decades, then to sticky inflation and constant recession chatter. In that mess, a lot of portfolios ended up with the same problem: overly concentrated equity risk and highly volatile returns, while traditional government bonds did not always hedge as expected. Against this backdrop, infrastructure bonds quietly moved from a niche idea to a mainstream way to get relatively stable cash flows tied to real‑world assets like roads, data centers, airports and renewable power. They are not magic, but as a safe diversifier they solve a few very specific pain points that have appeared in recent years, especially for long‑term investors trying to lock in real yield without loading up on equity beta.

Between 2022 and 2024, global infrastructure debt assets under management grew from roughly USD 900 billion to around USD 1.2 trillion, according to large industry surveys, with annual fundraising for dedicated infrastructure bond funds doubling over that period. At the same time, typical investment‑grade infrastructure bond yields in developed markets widened from about 2–3% in 2021 to the 4–6% range by late 2024, as base rates rose and credit spreads stayed reasonably healthy. That combination of higher coupons, relatively low default rates and some inflation linkage is exactly what many investors were searching for while dealing with equity drawdowns and volatile public credit spreads.

What exactly are infrastructure bonds and why are they “safer”?

At a high level, infrastructure bonds are fixed‑income securities backed by long‑lived, essential assets: toll roads, regulated utilities, ports, fiber networks, hospitals, energy pipelines, solar and wind parks. The cash flows often come from either regulated tariffs, long‑term concession agreements or long‑dated power‑purchase agreements. From a credit‑analysis standpoint, the key feature is visibility of cash flows: when you can reasonably forecast demand and pricing for 20+ years, you can model debt service coverage with much higher confidence than in a typical corporate issuer exposed to intense competition or fast product cycles. This is why many investors treat them as safe fixed income investments; infrastructure bonds historically exhibit lower default rates and higher recovery values than generic corporate bonds with the same rating bucket, especially in regulated utilities and transport concessions.

Safety here is relative, not absolute. Infrastructure bonds still carry interest‑rate risk, regulatory risk and sometimes construction or demand risk. But the probability distribution of outcomes tends to be tighter. Even during the COVID shock of 2020–2021, when airport traffic collapsed and oil demand plunged, rated infrastructure debt experienced materially fewer defaults than high‑yield corporates, and many assets continued to service their debt thanks to availability‑based contracts or regulated revenue models. For investors trying to stabilise portfolio volatility post‑2022, this profile made infrastructure bonds investment opportunities increasingly compelling compared with more cyclical credit exposures.

Recent 3‑year statistics: performance, risk and flows

From 2022 to 2024, the macro environment was dominated by inflation and rate hikes, which actually improved the forward‑looking attractiveness of infrastructure debt. In 2022, infrastructure bond indices had negative total returns (mid‑single digits drawdowns in many markets) mainly due to duration effects as yields spiked. However, credit spreads held up relatively well, and by early 2023 yields on high‑quality infrastructure paper had reset 200–300 basis points higher than pre‑COVID levels. For example, investment‑grade European utility and transport bonds maturing 7–10 years that had yielded around 1–1.5% in 2020–2021 were frequently trading in the 3.5–4.5% range in 2023, while similar tenor North American deals often printed at 4.5–5.5% or more.

Default and loss data over this period remained benign. While exact numbers vary by provider, aggregated studies up to 2023 show annualised default rates for rated infrastructure debt generally below 1% and often a fraction of that in the investment‑grade space, with average recovery rates in many cases above 60–70% when defaults did occur. Compare that to broader corporate high yield, where 2023 default rates in some sectors exceeded 3–4%, and the relative resilience becomes obvious. Capital flows followed the data: between 2022 and 2024, annual fundraising into infrastructure debt and infrastructure bond funds for diversification more than doubled, with insurance companies, pension plans and even retail‑oriented mutual funds ramping up allocations as they sought long‑duration assets to match liabilities.

Core problem: how to diversify without sacrificing yield or safety

Many investors who piled into long‑duration government bonds before the rate hikes discovered a nasty trade‑off: safety from default didn’t protect them from mark‑to‑market losses, and in real terms their purchasing power eroded. Equity heavy portfolios, on the other hand, suffered violent drawdowns in 2022 when central banks tightened aggressively. The pressing problem has been: where to park capital for 5–15 years in a way that delivers decent cash yield, controlled downside and genuine diversification from both equity risk and generic credit beta. Conventional investment‑grade corporate bonds offer some of this, but at the cost of exposure to highly cyclical sectors and business models that are not always resilient in stagflation scenarios.

Infrastructure bonds address this diversification gap by linking debt service to essential services and often regulated or contracted revenue streams. Tolls, electricity transmission fees, water tariffs or contracted data‑center capacity do not disappear in a recession, and usage often correlates more with population and economic structure than with quarterly GDP noise. That doesn’t make them recession‑proof, but it does reduce cash‑flow volatility. For an allocator designing a strategic fixed‑income bucket, adding a 10–20% slice of carefully selected infrastructure bonds can materially change the risk composition, reducing correlation with broad corporate indices and improving downside resilience while keeping yield close to — and sometimes above — standard investment‑grade bond portfolios.

How to invest in infrastructure bonds without overcomplicating it

If you’re wondering how to invest in infrastructure bonds in practice, there are three main routes: direct bond purchases in public markets, pooled vehicles (mutual funds and ETFs) and private or club deals often accessible through specialist managers. For most individual investors and smaller institutions, diversified pooled vehicles are the sensible default, because sourcing, analysing and monitoring individual project bonds is data‑intensive and requires sector expertise. Publicly listed funds that focus on regulated utilities, transportation, energy infrastructure and digital infrastructure allow you to gain exposure with modest ticket sizes, daily liquidity and transparent pricing.

Direct bond selection can make sense for investors comfortable with credit analysis and minimum lot sizes, especially if they want to build a laddered portfolio to match specific liability profiles. You’d typically start by filtering for investment‑grade issuers in core infrastructure sectors, then analyse covenants, revenue models (regulated vs. demand‑based), leverage metrics and interest‑coverage ratios. In both cases, paying attention to duration is crucial after the 2022–2023 rate shock: a mix of short‑ and intermediate‑term bonds combined with some long‑dated regulated utility debt can deliver a balanced interest‑rate profile while still capturing infrastructure’s structural advantages.

Real case: pension fund derisking after 2022

Consider a mid‑sized European pension fund that entered 2022 with 55% in equities, 35% in government bonds and 10% in generic investment‑grade credit. The sharp rise in yields delivered a double hit: bond prices fell and equities sold off, while the fund’s liability discount rate rose only slowly. In 2023, the investment committee decided to re‑engineer the fixed‑income sleeve. They cut generic corporates from 10% to 5% and increased long‑duration infrastructure debt from 0% to 10%, mainly via global infrastructure bond funds that targeted regulated utilities, renewables and transport concessions with average BBB+ rating and 8–12 year duration.

By late 2024, internal performance attribution showed that the infrastructure bond allocation had contributed roughly a third of the fixed‑income income return, with volatility significantly below both the equity book and the legacy corporate credit holdings. Drawdowns during rate spikes were still there, but the mark‑to‑market swings were smaller than in the sovereign portfolio due to a combination of higher coupons and tighter spreads. On a scenario basis, the risk team also reported improved resilience under “low‑growth, higher‑for‑longer rates” simulations, demonstrating that, for this fund, infrastructure bonds were not just another credit sleeve, but a distinct safety anchor.

Real case: family office hunting for yield without leverage

A different example comes from a Latin American family office managing multi‑generational capital. After years of relying on leveraged real‑estate deals and high‑yield corporates, they wanted to reduce leverage while keeping a net portfolio yield near 6%. In 2022, that looked unrealistic with safe assets. However, by 2023, as policy rates surged, the office began rotating into a mix of listed infrastructure debt funds and a few carefully screened dollar‑denominated project bonds linked to renewable energy and port facilities. Duration was kept moderate (5–7 years) and credit quality hovered around BBB.

Over the next 18 months, the office gradually moved roughly a quarter of its fixed‑income book into infrastructure bonds, both public and private. The resulting blended portfolio yield landed around 5.5–6%, but with significantly lower leverage and less exposure to cyclical corporate earnings. Stress tests against 2008‑style credit shocks still showed vulnerability — nothing eliminates risk — but cash‑flow projections were far more stable, helping the family meet distribution needs without constantly selling assets in bad markets. This kind of shift encapsulates why many investors now see the best infrastructure bonds to invest in as a pragmatic middle ground between ultra‑safe sovereigns and more nervous high‑yield names.

Non‑obvious decisions that separate average and strong outcomes

The straightforward approach to infrastructure debt is to buy a broad fund and move on. That’s better than ignoring the asset class, but a few less obvious choices can meaningfully improve risk‑adjusted returns. One is to pay attention to the mix of regulated vs. volume‑exposed assets. Regulated utilities and availability‑based public‑private partnerships behave almost like quasi‑sovereign risk in many jurisdictions, whereas demand‑based toll roads, airports or merchant power projects embed more economic sensitivity. Blending the two gives you a more diversified driver set, which matters when you want uncorrelated behaviour relative to your traditional corporate bond book.

Another subtle lever is inflation linkage. Some infrastructure bonds have explicit inflation‑indexed tariffs or periodic pass‑through mechanisms written into concession agreements or regulatory frameworks. Others operate in markets where pricing power is strong enough to maintain real margins over time. During 2022–2024, as inflation rose, investors who had done the work to identify such structures were more comfortable holding longer‑duration paper, because they believed real cash flows would be partially protected. This is especially relevant for long‑term allocators like insurers or endowments who need to think in decades, not quarters.

Alternative ways to get infrastructure debt exposure

Beyond buying bonds directly or through traditional funds, there are several alternative methods to access the same underlying economic engine. Private credit funds specializing in infrastructure debt lend directly to projects or asset companies, often at slightly higher spreads than public markets in exchange for lower liquidity. Some insurance‑linked products and structured notes repackage diversified pools of infrastructure loans and bonds into tranches with specific risk/return profiles; these can make sense for investors with strict capital constraints or regulatory capital charges. In some cases, green bonds and sustainability‑linked bonds issued by infrastructure operators also offer exposure while aligning with ESG policies.

For investors willing to tolerate even less liquidity, co‑investments or club deals alongside infrastructure equity sponsors provide tailored deb‑like exposure with negotiated terms, such as enhanced covenants, security packages or step‑in rights. While these are not for everyone, they can be powerful tools for large institutions seeking yield enhancement without jumping straight into equity risk. When properly structured, they still function as part of the safe fixed income investments infrastructure bonds universe, but with bespoke features such as cash sweep mechanisms or maintenance reserve requirements that further protect bondholders.

Practical checklists and lifehacks for professional allocators

Professionals looking to implement infrastructure bonds at scale tend to obsess over a few recurring themes: credit governance, legal structure, regulatory risk and correlation management. Even if you outsource manager selection, it’s worth having a clear internal framework. The goal isn’t just to chase yield; it’s to insert a stable, predictable cash‑flow engine into the portfolio without accidentally importing concentrated regulatory or political risk. That means interrogating where the cash actually comes from, how it is protected in contracts and how it might behave under stressed macro scenarios, something credit committees often under‑resource when they assume “utility = safe”.

A practical starting checklist could include:

– Revenue model: regulated tariff, long‑term offtake contract, availability payments or merchant risk?

– Capital structure: leverage levels, debt service coverage ratios, ranking vs. other creditors, presence of structural subordination.

– Legal protections: covenants, security package, step‑in rights, change‑in‑law protections, termination compensation formulas.

– Macro sensitivity: exposure to GDP, traffic volumes, commodity prices or technological obsolescence (e.g., older data‑center designs, legacy pipelines).

Beyond basic diligence, there are a few tactical “lifehacks” that experienced investors quietly apply:

– Use infrastructure bonds as a rate‑hedging tool: in rising‑rate environments, favour shorter‑duration or floating‑rate infrastructure loans; in stabilising or falling‑rate regimes, extend into longer‑dated regulated utilities to lock in higher real yields.

– Exploit vintage diversification: stagger commitments across multiple years and deal cohorts, especially in private funds, to avoid concentration in a single pricing and regulatory cycle.

– Cross‑region balancing: pair developed‑market regulated utilities with carefully selected emerging‑market infrastructure bonds, where spreads compensate for political risk, to create a blended risk premium that outperforms homogenous portfolios over cycles.

What to watch out for: key risks and common mistakes

Calling infrastructure bonds “safe” can be misleading if it encourages complacency. One of the biggest underappreciated risks is regulatory and political interference. A change in government can upend tariff formulas, delay indexation or alter concession rules, particularly in emerging markets but occasionally even in developed economies. Investors who bought certain European energy network bonds before surprise regulatory interventions learned this the hard way when allowed returns were revised downward. Mitigating this means going beyond ratings and reading the actual regulatory frameworks, historical track records of tariff resets and, where possible, independent legal opinions on change‑in‑law protections.

Another trap is construction and completion risk. Greenfield projects — new toll roads, ports, power plants — carry material risk of delays, cost overruns or technical issues, which can severely impact early cash flows. For many conservative portfolios, it’s cleaner to focus on brownfield, fully operational assets where demand patterns and operating costs are well understood. Finally, concentration risk can sneak in: buying several funds that all own the same big names in utilities and transport does not equal diversification. Mapping exposures across vehicles and looking through to the underlying issuers is essential if you want your infrastructure bonds to genuinely diversify rather than mirror your existing credit book.

Bringing it together in a modern portfolio

In the 2022–2024 environment of high inflation, aggressive rate hikes and geopolitical volatility, infrastructure debt quietly earned its place as a strategic building block rather than an exotic side bet. Infrastructure bonds investment opportunities now span the full risk spectrum, from ultra‑defensive regulated utilities to higher‑yielding emerging‑market transport and energy projects, enabling fine‑tuning of both risk and duration. When integrated thoughtfully, they can reduce overall portfolio volatility, enhance income and provide some insulation from purely cyclical corporate earnings, all while maintaining credit quality and transparency.

For many balanced portfolios, a pragmatic target is to treat infrastructure bonds as a distinct sleeve within fixed income — perhaps 5–20% depending on risk appetite — accessed primarily through diversified vehicles, complemented by selective direct bonds for those with the expertise. Among the various tools available today, infrastructure bond funds for diversification are often the easiest on‑ramp, especially if they clearly disclose sector, country and duration breakdowns. Used this way, infrastructure bonds won’t solve every problem, but they offer a rare combination that’s been in short supply over the last three years: predictable cash flows, defensible business models and yields that finally compensate you for the risks you’re actually taking.