International property sounds glamorous—coastal condos, city skylines, the whole postcard set. But if you strip away the brochure feel, you’re dealing with a very specific task: using foreign bricks and mortar to reduce portfolio risk and smooth returns. That’s what we mean by *investing in international real estate for diversification*: adding assets whose cash flows and price cycles don’t move in lockstep with your home market. When it’s done well, you get exposure to different interest‑rate regimes, demographic trends and currencies, instead of betting everything on one national housing cycle or one central bank’s policy mistakes.

Scale, statistics and why cross‑border flows matter

Global real estate is not a niche. Various industry sources estimate the total value of professionally managed real estate at over 13–15 trillion USD, and cross‑border deals routinely account for roughly a quarter of institutional transaction volume in a normal year. After the pandemic shock, capital flows started to recover, with international real estate investment opportunities shifting from saturated core offices toward logistics, data centres and rental housing. That pivot is important for diversification: sector mix is now as critical as geography, so “going abroad” increasingly means mixing different property types and regulatory regimes, not just buying another apartment, only this time with palm trees.

Comparing main approaches: direct ownership vs listed vehicles

If you’re trying to understand how to invest in international real estate for diversification, the first fork in the road is *how much control* you want versus *how much operational pain* you can tolerate. Direct ownership of an apartment in Lisbon or a small warehouse near Warsaw gives you granular control over financing, renovation and tenant mix, but it drags in legal work, local tax nuances, property management and vacancy risk; you’re effectively building a micro‑business in a foreign jurisdiction. By contrast, buying shares in global REITs or specialized funds turns that into a securities play: you ride broad market cycles, delegate asset selection and accept daily price volatility on a stock exchange instead of dealing with plumbers in a different time zone. Economically, direct deals can offer higher idiosyncratic alpha, while listed vehicles trade closer to macro factors such as rates and equity risk sentiment.

Direct control isn’t the only game in town, though. A middle route is to use established international real estate investment companies or private funds that pool capital into regional or thematic strategies—say, “Asia‑Pacific logistics” or “European student housing.” Here, you sacrifice liquidity and accept management fees in exchange for professional underwriting, local networks, and institutional‑grade due diligence you probably couldn’t replicate. It’s still real estate, but you experience it through quarterly reports and capital calls rather than hunting for a notary who speaks your language.

Economic mechanics: correlations, currency and macro cycles

From an economic‑theory angle, diversification value comes from low or imperfect correlations between asset returns. Residential prices in Canada, rental yields in Eastern Europe and cap rates on Japanese multifamily do not respond identically to global shocks or domestic policy. Historically, cross‑country real estate correlations have risen during crises but remained well below 1 over full cycles, which means foreign holdings can still dampen portfolio volatility. Add currency into the mix and the story becomes more nuanced: foreign cash flows can hedge or amplify macro risks depending on your home currency and liability profile. For example, an investor earning in euros but owning USD‑denominated rental income might partially hedge against local inflation or policy mistakes by the ECB. Conversely, unhedged currency exposure can turn mild local price declines into painful drawdowns when exchange rates move the wrong way.

At the same time, you have the interest‑rate channel. Property values are essentially discounted cash‑flow streams, so different central bank cycles create staggered opportunities. When your domestic market is already repriced for higher rates and compressed valuations, another region might still be mid‑cycle, with room for yield compression and capital gains. This asynchronous monetary policy environment is one reason international real estate investment opportunities continue attracting institutions that already own plenty of domestic assets—they are not just chasing yield, but also diversifying rate‑cycle timing.

Country selection, statistics and forward‑looking themes

The question “best countries for real estate investment 2025” doesn’t have a one‑size answer, but we can dissect it into drivers: demographic growth, urbanisation, supply constraints, political stability and rule of law. Forecasts from multilateral institutions suggest that emerging markets in Asia and parts of Africa will continue to lead population and urban growth, feeding demand for logistics, mid‑market housing and infrastructure‑linked assets. Meanwhile, several developed markets with chronic housing undersupply—think selected cities in the US, UK, Germany, Australia—are likely to see rental tension persist even if price growth flattens. On the risk side, climate‑exposed coastal areas and jurisdictions flirting with aggressive rent controls may deliver more volatility than headline yields suggest. For a diversification‑minded investor, that means mapping not just GDP projections, but also zoning pipelines, green‑transition capex and migration flows over a 5–15‑year horizon.

In practice, the country “ranking” often matters less than the *fit* with your existing portfolio. If you’re already overloaded with cyclical tourist hubs, another holiday‑rental jurisdiction—even if statistically attractive in 2025—adds more of the same risk. Pairing defensive, regulation‑heavy markets with faster‑growing but less predictable ones usually produces a more balanced risk‑return profile than simply chasing wherever capital is currently flowing.

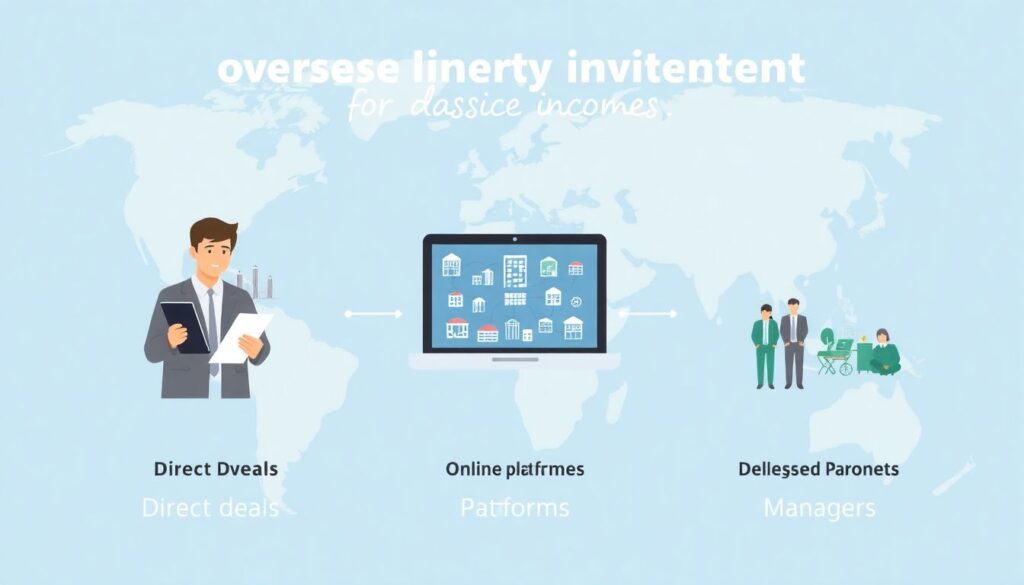

Hands‑on vs platform‑based: executing a diversification strategy

On the ground, you can pursue overseas property investment for passive income through three main channels: doing your own direct deals, using platforms like cross‑border crowdfunding or fractional ownership, or delegating the whole process to managers and companies. The direct path suits investors who can commit significant capital and time to due diligence, including site visits, legal opinions and tax structuring; here, diversification arises from bespoke deal selection—different tenant bases, lease structures and micro‑locations. Crowdfunding and fractional platforms lower the ticket size and allow broad geographic spread, but you concentrate platform and governance risk: you must trust that underwriting is robust and that alignment of interest is real, not just marketing copy. Delegated solutions via funds and managers compress your decision to manager selection and strategy choice; you get exposure to dozens or hundreds of assets but become reliant on someone else’s risk controls and leverage policy.

Whichever route you choose, the diversification benefit is only real if the underlying exposures are genuinely distinct from what you already hold. Buying a highly levered global REIT that owns mostly the same type of city‑centre offices you already have via a domestic vehicle adds complexity but not much diversification. The implementation question is less “Which product is trendy?” and more “Which structure gives me different cash‑flow drivers, legal systems and tenant behaviours without creating concentrated operational risk I don’t understand?”

Industry impact and the role of professional intermediaries

As more capital hunts international real estate investment opportunities, the industry itself changes. Transaction data show a growing share of cross‑border money coming from pension funds, insurers and sovereign vehicles that want long‑duration, inflation‑linked streams. Their need for scale has accelerated the professionalisation of property management, reporting standards and ESG disclosure requirements, particularly in markets that historically relied on opaque local practices. The rise of global managers and international real estate investment companies has, in turn, made it easier for smaller investors to access institutional‑grade portfolios indirectly, but it has also intensified competition for prime assets, compressing yields in gateway cities. For diversification, this creates a paradox: the more globally integrated major markets become, the more their cycles can synchronise, pushing investors to look at secondary cities, alternative sectors and niche strategies—senior living, self‑storage, data infrastructure—to maintain low correlations.

From a macro perspective, sustained cross‑border flows can stabilise some markets—by broadening the investor base and deepening liquidity—while arguably overheating others where foreign demand outpaces local income growth. Regulators are increasingly aware of this, introducing targeted taxes or ownership limits in certain residential segments. For an individual investor, that regulatory feedback loop is another variable in the diversification equation: jurisdictions that welcome foreign capital today may recalibrate incentives if affordability or political narratives turn. Building a robust international real estate allocation therefore isn’t just about picking “where it’s hot now,” but about stress‑testing how each market, and the industry around it, might behave under pressure over the next cycle.